Inquiry Project final report

Rebecca J. Foster

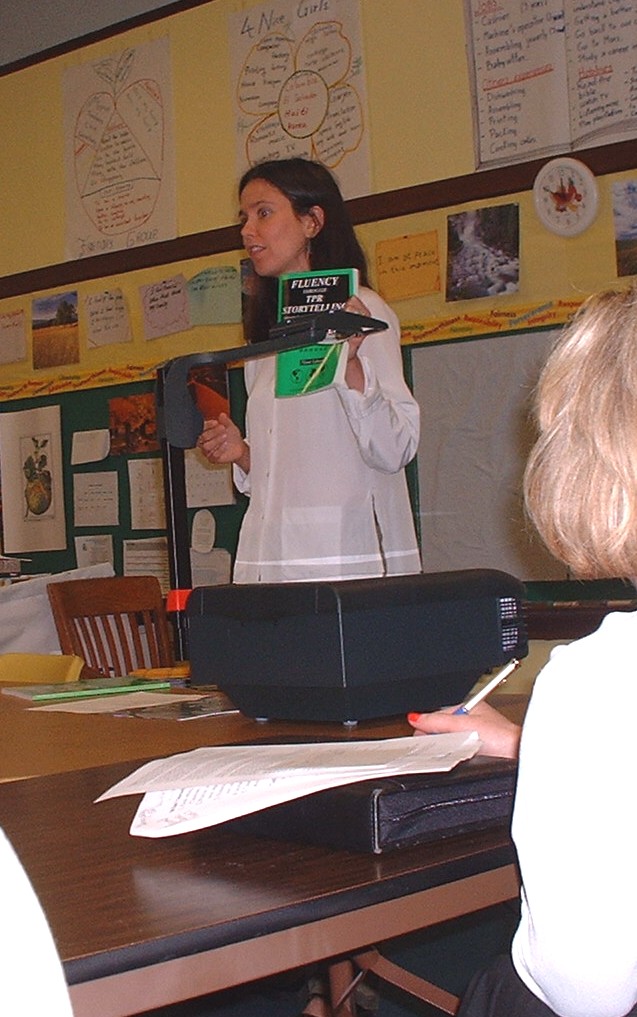

photo: Kristen McKenna

| Participatory TPRS:

Integrating the Participatory Approach with

Total Physical Response Storytelling

Inquiry Project final report Rebecca J. Foster photo: Kristen McKenna |

|

INTRODUCTION

During the 2002-03 school year, I taught beginning ESOL to adults at the Genesis Center in Providence, Rhode Island. This was my second year at the Genesis Center, and also my second year formally teaching ESOL. While I am a fairly "green" teacher, I have had many professional and volunteer experiences that inform and support my teaching. I have worked on projects ranging from HIV prevention to rural education in a variety of countries in Latin America, Southeast Asia and Africa. I taught English as a volunteer for a number of years, both at the Genesis Center as well as at two secondary schools in the rural highlands of Guatemala. I also currently serve on the board of English for Action, a local language school committed to participatory-based learning.

As a relatively new teacher, I am still exploring my beliefs in the classroom. I find the traditional grammar-based approach severely limited in terms of improving learners' ability to actually communicate. As such, I believe strongly in the communicative approach (activities designed to ensure genuine communication) as a way of building language skills. I also believe in using learners' lives and opinions as a central feature of class content in order to ensure that topics are relevant and, ultimately, empowering for learners. Just over a year ago I was introduced to the Total Physical Response Storytelling (TPRS) method, which sparked an interest in learning more about and incorporating this method into my own teaching.

The following report describes my experience trying to bring two of these approaches, participatory learning and TPRS, together. Specifically, it sets out to answer the question, "What happens when I incorporate a participatory TPRS approach in my classroom?"

THE STORY OF THE QUESTION

The story of this question begins with the central problem that I faced last year: how to increase language acquisition in an adult ESOL classroom while keeping the classroom content relevant to my learners' lives. I had been incorporating a variety of participatory elements into my classes, including sharing learner news via a class newspaper, initiating conversations on provocative topics, encouraging learners to choose themes to cover, and using the language experience approach (or LEAs) to write about issues as they arose. Nevertheless, I was frustrated by the lack of progress my learners were making. Even those who seemed to grasp certain vocabulary or grammar concepts on their homework or tests, didnıt seem able to use those concepts effectively to communicate on the spot. Meanwhile, a colleague at the Genesis Center presented a workshop in the winter of 2002 on TPRS. The logic, creativity, and energy of the method excited me. Moreover, it seemed to directly address the "language acquisition" aspect of my problem. For those unfamiliar with the technique, TPRS builds on the classic Total Physical Response (TPR) approach by systematically using storytelling to create massive amounts of interesting and memorable comprehensible input.

At the time I was teaching two classes, one of which was a small work-site class of all Spanish speaking factory workers. I immediately began using the approach in this class, while continuing to read and research more about its implementation. I quickly noticed that the intensive TPR provided a solid memory device, particularly for those learners who had been making little to no progress in the class. I was able to draw on learners' lives at the factory for story details and always had learners play the part of the hero, both important aspects of traditional TPRS. Learners seemed to love the change in the class format and there seemed to be a marked improvement in their ability to communicate, particularly by those that had not previously been having much success. This was exciting for me, to say the least.

As the new school year approached, I hoped to bring what I had learned in this small, very cohesive classroom to the larger, multi-lingual and much more diverse classrooms at the Genesis Center. However, I struggled with the apparent conflict between TPRS, which is very teacher driven, and the participatory approach. In TPRS, a teacher presents vocabulary and creates stories from that vocabulary. Learner input is actively encouraged, but it is not whatıs driving the overall curriculum. The stories are intentionally exaggerated and bizarre (in order to support memory) and rarely address real life issues. Moreover, TPRS generally assumes that all learners speak a common language and have a common cultural experience. In the factory, it was easy to do quick translations is Spanish and to draw on their factory experience as a source for material. This would not be the case at the Genesis Center, which draws a much more diverse group of learners.

As such, I decided to figure out how to incorporate both of these approaches in a way that would build upon, rather than detract from, each other. By using the formal "inquiry" process, I felt I would have a perfect forum to explore, reflect in a systematic way, gain insight from fellow practitioners, and ultimately tease out the potential strengths and weaknesses of integrating these two methods.

My class at the Genesis Center met three nights a week from 6-8 p.m. The night-program, which is funded through a labor-related grant, focuses on work themes, while also covering a wide range of life skills. I had roughly 20 learners in my classroom. They were mostly Spanish speaking but not entirely (the two other languages being Cambodian and Portuguese). While all categorized as beginners, all but the one Cambodian had taken at least some English (either during the short summer session or the entire school year) prior to the class. As such, learners' English skills were fairly multi-level. Ages ranged from early 20s to late 50s. There were quite a few strong personalities (highly opinionated, talkative, and at times aggressive) in the classroom and the noise level often got quite high. The climate was relaxed and playful, and at times fairly boisterous.

As the year progressed, my essential question-- "what happens when I incorporate a participatory TPRS approach in my classroom?" -- remained the same. While the details of what I termed a "participatory TPRS approach" evolved over time, the essential elements of the approach I used in the classroom included the following:

DATA COLLECTION METHODS

I chose at the outset to use the following six data collection methods:

1. Keeping daily field notes using the "sample card" method. This method involves identifying a variety of relevant themes and randomly choosing a theme each day. At the end of each class I would take a few minutes to write about the chosen theme. My sample card themes were:

2. Keeping weekly field notes using Brookfield's questions. These five questions ask you to identify when you were most and least engaged during the week as well as the classroom activities or moments that were most affirming, puzzling and surprising.

3. Surveying learners monthly regarding various classroom activities in general and the different TPRS stories in particular. Surveys were one page and very easy (learners had to circle a happy face, a neutral face or a sad face for each activity or story).

4. Using the Language Experience Approach (LEA) at the end of each week to talk about the weekıs activities as well as concepts and themes covered. The purpose of this method was to gage learnersı own perception of what was happening in the classroom on a weekly basis.

5. Asking several learners to write weekly, in English or own language, how they were perceiving/feeling about the class.

6. Filming my TPRS teaching once a month. This, I hoped, would provide a more objective look at what was taking place.

I was most successful with the first two of these methods (sample cards and Brookfield's questions) which I completed diligently throughout the year. I also completed the surveys and weekly LEAs, however they both provided much less insight than I had hoped. As such, towards the end of the year I tended to use these methods less regularly. Unfortunately I had a very difficult time getting learners to write (in any language) about their perceptions and feelings about the class. I gave journals out, thinking this would encourage them, but in the end I only got a few back. Most of these seemed to be ardently convincing someone (presumably a boss) that I was a good teacher. Finally, due to technical and logistical difficulties I was only able to film two TPRS stories. This was decidedly frustrating as I very much wanted to film more. Nevertheless, the video clips did serve as useful feedback mechanisms, pinpointing weaknesses and strengths of my overall TPRS technique.

Despite these pitfalls, the data collection methods produced a great deal of data that collectively paints a fairly detailed picture of what happened when I incorporated participatory TPRS in my classroom.

FINDINGS

Challenges of "Participatory TPRS"

It was relatively easy to use both participatory techniques and TPRS in the same classroom at least separately. In one sense, the two methods were complimentary, together addressing my two main classroom objectives (to facilitate as much learner language acquisition as possible while also giving learners a forum to share, discuss and address issues of concern to them in their daily lives). As such, it was natural for me to move from the spontaneous learner centered "class news" to targeted intensive TPR with out much need for a link between them.

However, my goal of explicitly integrating the two pedagogies presented a number of distinct challenges. One of the most obvious was that while a participatory curriculum is learner driven, classical TPRS is primarily teacher driven (though with considerable input from learners as well). Normally in a participatory classroom, the teacher prompts learners to articulate relevant problems and/or issues that generate the vocabulary and activities/actions that follow. Conversely, classical TPRS requires an unfolding of vocabulary through small stories that together build up to a larger story incorporating and reinforcing the previous vocabulary. To make this work, I needed to have some initial sense of the vocabulary I would later use and how it would ultimately fit together into a longer story. This premeditated vocabulary list thus limited my ability to be responsive to learner discussions. Similarly, responding to and building on learner discussions limited my ability to move systematically through the stories (which provide the basic structure for the massive amounts of comprehensible input intrinsic to the TPRS method).

Another incongruity I encountered is that one of the tenets of classical TPRS is that the more bizarre the story, the better the learner acquires the vocabulary. That is, a story that is truly bizarre provides a stronger "memory hook" for the vocabulary than a mundane story. For example, a story about Elvis Presley buying a peanut butter and banana sandwich for $1,346 dollars from an elephant named BooBoo, provides a stronger memory hook for the word sandwich than a story about a man who buys a sandwich everyday for lunch. However, given my commitment to the values of participatory learning, I very much wanted to keep the material as realistic and relevant as possible to learners' lives.

While I struggled with these issues in my efforts to integrate the two methods throughout the year, constantly adjusting the balance and emphasis, I eventually came to following strategies that seemed to fit learner interests without dismantling the basic structure of TPRS.

Identifying Themes

After a few frustrating weeks of trying to explicitly link stories to learners' lives, I decided instead to use the weekly news and other more participatory-based activities to identify general themes of interest and problems relevant to learnersı lives (see Appendix A for an example of the weekly newspaper). I then used these general themes to develop lists of vocabulary that would drive the storytelling structure. While this process lacked some of the spontaneity and action orientation of the participatory model, it nevertheless ensured that at the very least the stories would genuinely reflect learner interests and concerns.

Learner Input

Classical TPRS actively encourages learners to generate many of the details of the stories, drive plot twists and sometimes take full control of the stories. As a TPRS teacher, learning to let go of a story is actually a key element of the instruction process. While hardly fitting the Freirian model of learner-led social action, this input nevertheless gave many opportunities for learners in my class to be creative and take ownership over their class material. Learners always expressed considerable satisfaction (smiling, clapping, etc.) upon coming up with the perfect detail for a story. My favorite examples of this were the times when I simply could not come up with a plot at all, at which point one of the more vocal learners would put the whole story together with great enthusiasm and pride. One woman was particularly adept at this, with stories ranging from explosions at gas stations due to a tossed cigarette to challenging a boss over an incorrect paycheck.Personalizing the PMS

Because the daily "Personalized Mini-Stories (PMS)" (short stories about learners based on three new vocabulary words or phrases) are generally created on the spot, there is quite a bit of room for spontaneity within them. As such, whenever possible I tried to set the PMS up to reflect some aspect of current learner reality, whether it be an event, a relationship or a situation. Two or three sentences are hardly enough for a deep provocative story, but nevertheless, many of our PMSs this year at least reflected learners' lives in some way and at times fostered further discussion on the theme.Learners as Heroes

Classical TPRS always attempts to set learners up as heroes of the stories. I found this to be particularly important in the ESOL classroom. Indeed, learnersı reactions to stories were almost always strongest when a classmateıs bravery, kindness or intelligence was highlighted. For example, one of their favorite stories was about a very shy young man from Guatemala in the class. In the story, he plays a reporter for Telemundo in Iraq who narrowly escapes a bomb explosion to give his daily report (See Appendix B for story text). Learners loved to tell the story (smiling, laughing, interjecting) and gave a number of impromptu comments like, "very good class tonight teacher!" when we finished. Interestingly, prior to that story this shy young man never said a word in class. While the events may be unrelated, this story definitely marked the beginning of his increased interaction and participation in class. In general, I found that using learners as heroes-- even if only in fictional situations-- provided important reinforcement of learnersı positive identity as problem solvers.Details and Surprises

As my stories evolved throughout the year, I saw clearly that interesting details are indeed important to the TPRS method. Again and again I was surprised by learners' memory of the minute details of a story. For example, learners would always remember the exact number of days that Rafaela waited for her income tax refund or what specifically Maria needed to buy at the grocery store when she accidentally got her foot stuck in a railroad track. However, my efforts to include truly "bizarre" details almost always fell flat (so flat that I myself can barely remember those stories now!). Instead, I came to realize that the memory hook comes not so much from something that is "bizarre" but rather something that is surprising. For adult learners new to this country, there are already many things that are surprisingone need not reach out into the land of talking gorillas. A teacher in Colorado who is currently designing TPRS materials for the adult ESOL classroom validated this observation for me when we spoke on the phone: "A good memorable story needs to have a twist or a surprise but it doesnıt have to be bizarre. For adult ESOL learners, life in America is already bizarre enough."In my class, the best stories this year all tended to have some sort of surprise. For example, in "Paulino's Accident," the surprise comes when a classmate visits him in the hospital and gives him some beautiful yellow flowers. Paulino, who was blinded in the accident, is so happy that suddenly he opens his eyes and he can see again. The doctor exclaims, "I can't believe it!" Learners loved this story (see Appendix C for story text), and the phrase "I can't believe it!" stuck. At least once a class someone would say, whenever something surprising happened, "I can't believe it!"

Key Participatory Issues

Throughout the year, I was constantly listening to and recording themes as they arose. From these themes, I created vocabulary lists as well as a long ³chapter story² to go with it. Then, I introduced the new vocabulary using TPR and developed, with the help of the class, a PMS (short story) to go with it. The following is a list of the predominant themes and the types of stories or activities that emerged. In a few cases, when a specific problem or issue arose that did not fit into the TRPS structure given the relevant vocabulary, and/or when the issue needed to be addressed right away, we used the LEA format to talk about it and develop action steps rather than TPRS.

Sickness and Accidents

Probably the most recurring themes of all were sicknesses and accidents. In just about every class newspaper throughout the school year there is a least one mention of someone (learner, friend, family member, local or international news story) getting sick or having some sort of accident. I recognized the immediacy of this issue about mid-way through the year and began developing a list of relevant vocabulary. From this vocabulary the class created a variety of PMSs about various kinds of accidents, visits to the hospital and appointments with a doctor. We also did a great deal of TPR for various ailments, practiced calling in sick, practiced writing notes to teachers about sick children, and played games like "Dr. Simon" (ie., "Dr. Simon says you have a broken foot!"). I also used LEAs to write stories about a variety of local emergencies, such as the Station fire in Warwick, as well as personal stories that came up in class, such as a former classmate who fell down her front steps.

Unemployment, Looking for work, Wages

Another very common theme was work, and all too often, a lack of work. Many learners talked about finding jobs, losing jobs, spending months looking for jobs as well as wanting more pay for their current jobs. Again, I created a list of relevant vocabulary and the stories followed. For example, one story was about a learner who comes to the USA and interviews for a job at a gas station. Another story was about a learner who loses their job but calls Dee Dee (the Genesis Center job placement counselor) for help. In another story, (created entirely by a learner around the phrases, "you're lying," "it's not fair," and "a better job,") a learner discovers that sheıs being underpaid for her overtime and confronts her boss (see Appendix D for story text).

War

The war in Iraq was a constant theme throughout the year. Learners for the most part expressed concerns about their own safety vis-à-vis terrorism (the risk of which they felt increased due to the war) as well as the safety of relatives or friends serving as soldiers. During the height of the combat, learners talked daily of the latest events, expressed outrage at Saddam Hussein, as well as frustration regarding domestic issues (primarily jobs) that were being ignored at home. During the class we used both mind maps and the LEA process a great deal to process these events. We also created perhaps the best story of the year about a learner as a reporter for Telemundo in a building hit by a bomb.

Other Learner Issues

Occasionally a learner would arrive with a serious problem or concern that needed to be addressed right away. For the most part, I relied heavily on the LEA process in these cases to discuss the relevant issues and develop action steps. For example, one learner had a hearing impaired son whose teachers kept losing the microphone for his hearing aid. Her son was at risk of not graduating, in part because he couldn't hear his teachers. The school refused to do anything about it. The class talked at length about what might be done, ranging from going to talk to the principal to calling the Providence School Department. In the end, we identified the name of her sonıs Special Ed coordinator and, after going to the school with her oldest daughter, she was able to get the school to buy a new microphone (see Newspaper, Appendix E).

In specific cases like this, I felt it was important to skip the TPRS story of the day and use a more participatory method to address the issue. TPRS simply does not provide enough flexibility to sufficiently address immediate and specific learner needs.

back to inquiry main page